Texts

La muntanya al teu voltant © Borja Ramos

Borja Ramos: Vivid artistic and musical ramifications Joaquim Noguero

In a broad and precise portrait of Marlon Brando (“The Duke in his Domain”), Truman Capote recalls the strange mismatch he seemed to find between the face and the body when he first saw the American actor, a rare mixture of angel and trucker, as if beauty and beast had been integrated into a single organism, in a dangerous and trembling presence of winged unicorn.

The best artistic creation combines the immateriality of the most creative shared echoes with the contrast of the tremendously physical base provided by the craft and the materials it polishes; everything worked organically, fused into a natural body, integrated into a coherent corpus of collective, communal vocation. This is how I see the music of Borja Ramos (Barakaldo, Spain, 1973). Also during the interview, I experience a strangeness very similar to that pointed out by Capote, in view of the distance between the vocal sound and the physical appearance of the Basque musician adopted by Catalonia. The fine youthful appearance contrasts with the roughness of the granite and raspy voice: a hoarse baritone register that expresses itself with radical clarity, breaking up the voice but connecting all the ideas with an expressive efficacy without measure. It is a young but deep voice, humble in its pronouncements but deep in what it explains, with echoes of an old cave that does not make strange assumptions about the one it makes: the music it composes for others from very diverse interests, with a clear commitment to give itself, to be heard and felt.

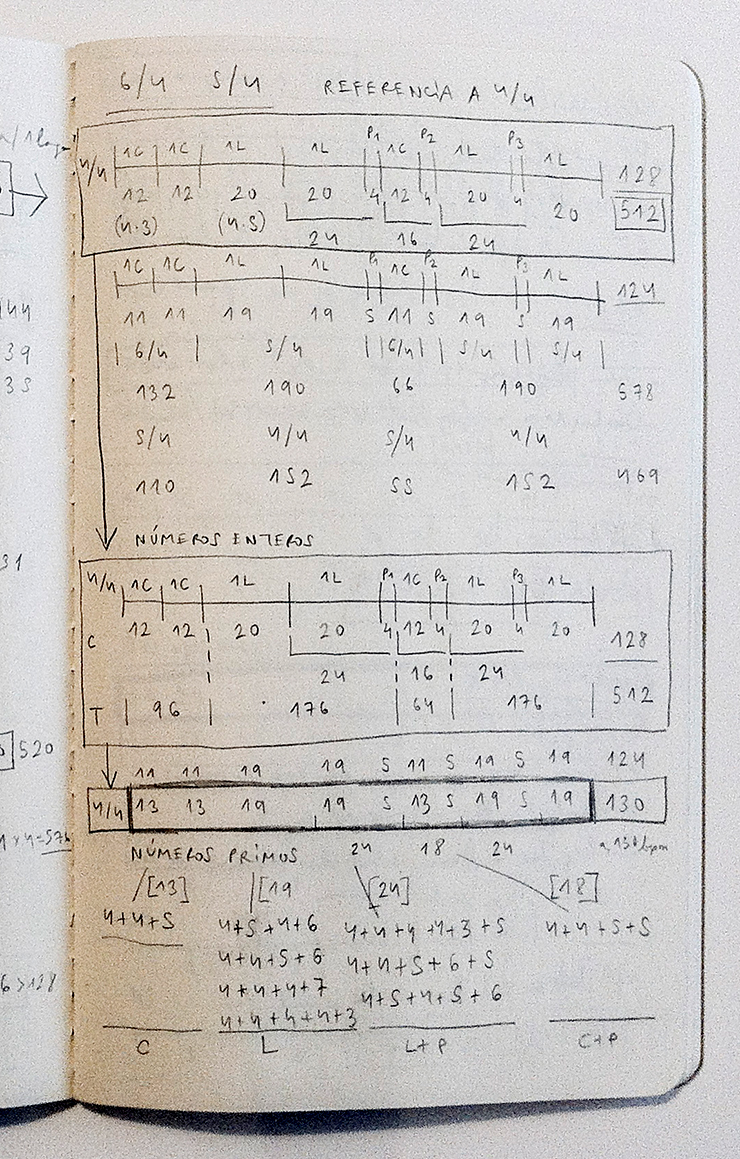

Thus, the clarity he often achieves with four bare notes contrasts sharply with the dense body he seeks in the orchestration or the different electro-acoustic textures. Today, Ramos enjoys music that is as direct as possible, but that doesn't give up anything. He works with computers, the score and the performers, any of these three areas can serve as a starting point. In fact, computers and electro-acoustics interest him in order to set horizons, to explore possible sounds that he then seeks to elaborate with the orchestra and with specific musicians. “I prefer to work with people (there is a very creative point of uncertainty in the performance, in what they will bring to the table, whether you like it or not), but what I do find interesting about computer tools is that they help you imagine music that would be very difficult to conceive of on your own. They allow you to imagine certain textures, harmonies, polyrhythms, etc., which are very complex; at first, you conceive it mentally, looking for a fragile balance between chaos and understandable complexity, but it is difficult to translate this into the form of notes and, on the other hand, thanks to the computer you can hear more or less how it will sound. It also allows you to pose reading and writing problems to the musicians that, if you hadn't first tried what they can do, you would hardly dare to raise”. Here the musician likes to recall a significant anecdote by Gustav Malher that he read in Alex Ross' book, “The Rest Is Noise”. It is about a time when Mahler supported Arnold Schoenberg and in a letter he confesses that when he read the dodecaphonic scores of the Viennese “I could not feel them inside my head, I could not hear them mentally“. But he added: “in spite of this, I think it is the music of the future”. For Ramos, when Mahler saw Schoenberg's score, “he couldn't hear it because it was such a different writing music that it was out of his mind. Well, this happens very often to us composers today: music is more and more complex, it plays with many more elements than a traditional score and, when faced with some compositions, even conductors have trouble imagining them if they do not first approach them with computers to get closer acoustically to what the composer intended and thus be able to conduct the orchestra”. Conceived in this way, as a tool and not as an end, computer science comes to be a type of mechanical exoskeleton to help our always human and weak cerebral musculature: at the beginning it allows to load more tons on the shoulder of the notes, but at the end the work always has to be directed by the head, the architect capable of solving thousand fantasies and possibilities of combination on all these extra kilos.

Art and dance

Trained in Valencia in audiovisuals at the Faculty of Fine Arts and in Electroacoustic Music at the LEA-Laboratory of Electroacoustics at the Conservatory of Music, Ramos had just studied Dramatic Art in Bizkaia and Applied Arts in Logroño. His training is therefore multidisciplinary. As a musician, he comes from the pop/rock world, specifically from the techno of the eighties, and was trained in contemporary music later on. When he heard the Austrian composer György Ligeti for the first time, he was a true discovery, and later he made his own the maxim of composing music that, no matter how much reference it has inside, is not noticed, is natural, organically integrated in the group. When working, Ramos has performed mainly in two fields: dance and film. In dance, he has composed for Gelabert-Azzopardi, for Germán Jauregui (a dancer with Wim Vandekeybus who is now beginning his own career as a choreographer) and for Damián Muñoz, to highlight especially three among some of the most representative choreographers of a long list that includes Víctor Ullate, the Madrid company 10 & 10 Danza, Asier Zabaleta, Natalia Medina, Idoia Zabaleta, Blanca Arrieta, Cristina Quijera or Larumbe Danza (with choreographer Teresa Nieto).

He began with Damián Muñoz in shows such as “Staff”, “El engaño en los ojos”, “Las mentiras del entusiasmo”, “Yo notaba la comida amarga...” and “Asiré, el futuro imperfecto del verbo asir”, as well as a part of “Daño”. For the Catalan choreographer Cesc Gelabert he has worked on “Orion”, presented at the Grec 2011 the work of deconstruction and recreation of the sardana “La muntanya al teu voltant” and a couple of months ago he has just premiered at the Teatre Lliure “Cesc Gelabert VO+”, the recovery of old solos by the choreographer for which he has composed three pieces that basically have the function of cementing the collage, a real challenge if we consider what it means to have had to stand next to Bach and survive the comparison with dignity and success. With the Catalan choreographer he works comfortably, because Gelabert knows what he wants, he arrives with the show already organized in his head, then, on the first guidelines and the joint table work leaves a wide margin of confidence. It is not always the same to work on demand. Ramos believes that first you have to establish a common vocabulary: “there are choreographers with more musical knowledge and others who are more intuitive; it is advisable to find a code to understand what is expected. What does it mean, for example, if someone asks for 'more expressive' or 'warmer' or 'brighter' or 'more dramatic' music? Sometimes, when you are told that a certain piece of music should be 'more dramatic', what the choreographer has in mind is simply that the music should be slower”. The piece “La muntanya al teu voltant” is full of references: it combines subjective fragments, seeking more or less universal emotional echoes, with others related to specific aspects of Catalan culture such as the sardana; at times Ramos creates with great freedom and at other times its function is basically that of glue, of glue to present the whole in a fluid way. “Once the music has been made, I can say very little about it, but what always surprises me in Cesc's case is the use he makes of it, how he taps into it, when you think that on a dense musical passage he would elaborate sophisticated, complex or group movements, he surprises you with a minimum solo, with a delicate gesture that enhances the emotions acting on that fragment”. Ramos works on the composition for dance thinking that it has to serve the dancers and the audience: the dancers have to find in the music an ally, it has to help them to better understand the deep nature of the scene; and the audience, no matter how demanding the choreography and even certain sections of the musical composition, has to notice a continuum. In the works, music plays the role of a dramatic backbone, structuring the work, arranging the perception and impressions. In this connection, he is now experimenting with the choreographer Germán Jauregui, when he is considering how certain music is placed before which sequences of movements absolutely condition the meaning given to them by each spectator. One can see that the audience matters to him: he does not feel that he can use a supposed freedom, creativity or originality as an excuse to distance himself. Creativity lies precisely in being able to take the spectator by the hand through the thousand paths that music offers today and to convince him to travel them together.

Hidden in the background (just as essential, but), we can find the works for film music. Mainly the feature films “Frágil”, by Juanma Bajo Ulloa, and “Nos miran”, by Norberto López Amado, as well as the electronic sections of “Kamchatka”, by Marcelo Piñeiro, “El arte de morir”, by Álvaro Fernández-Armero, and “Skin Deep”, by Sacha Parisot. It is not surprising that his ability to create atmospheric tones has been translated into genre collaborations. He has also collaborated with Basque singers such as Mikel Laboa, Ruper Ordorika and Mikel Urdangarin. And in the field of contemporary music he has worked with groups such as Sigma Project, the ensemble Espacio Sinkro, the Krater Ensemble and the ensemble Kuria, as well as participating in a lot of international festivals, both in contemporary music and in electro-acoustics, dance or theatre. The milestones in different directions outline the map of a complex territory that allows for diverse incursions. If it were possible to define it on the basis of his tastes, an important reference for him is the work of the German creator Heiner Goebbels (1952), a composer and director of stage and radio works who combines classical music with jazz and rock, first starting with Eislerian music and who has ended up composing for the cinema, theatre, dance and opera with a great capacity for reorganising the elements. Ramos emphasizes “musical theater”, where music is the center, and the musicians perform actions during the performance—not small gestures, as has been seen so often in contemporary works. In Goebbels' creations “the musicians really DO. They are the ones who assume and really carry out the dramaturgy”. The German works with fantastic musicians (those of the Ensemble Modern, for example), but what he finds most interesting is “the role he gives them”, and why and what for. “Goebbels understands that the contemporary Western spectator is highly educated and approaches the scene with his head full of references, clichés, conventions”, both conscious and unconscious, “a very rich code that has made him lose to a great extent his capacity to surprise, to be fascinated and to be surprised”. Goebbels' work consists of “dismantling this state of things, dislocating the spectator, presenting things in a different way, so that he can listen and look again”. Ramos gives the example of “Stifters Dinge” (Stifter's Things), a play presented at the Lliure Theatre in 2010 in which Goebbels combines five mechanized pianos, a lot of cables, three industrial pools, a video screen and a few robotic devices within a mobile structure without any performer on stage. “There was nobody, only machines doing things, and explained like this it may seem an empty artifice, but the development worked and was exciting because he is an intelligent, sensitive and fascinating creator who leaves no loose ends, in which nothing is meaningless. Goebbels seems to me a great reference for this commitment to the audience: to turn things around to make us feel the music and the scene as a virgin space again”. The German certainly represents a possible model, the example of someone who finds his freedom in the rigorous mastery of his expressive medium, fully aware of the environment in which he moves. And someone with his own language is someone who ends up sharing it with everyone, someone who branches out in this way. Like Ramos.