Texts

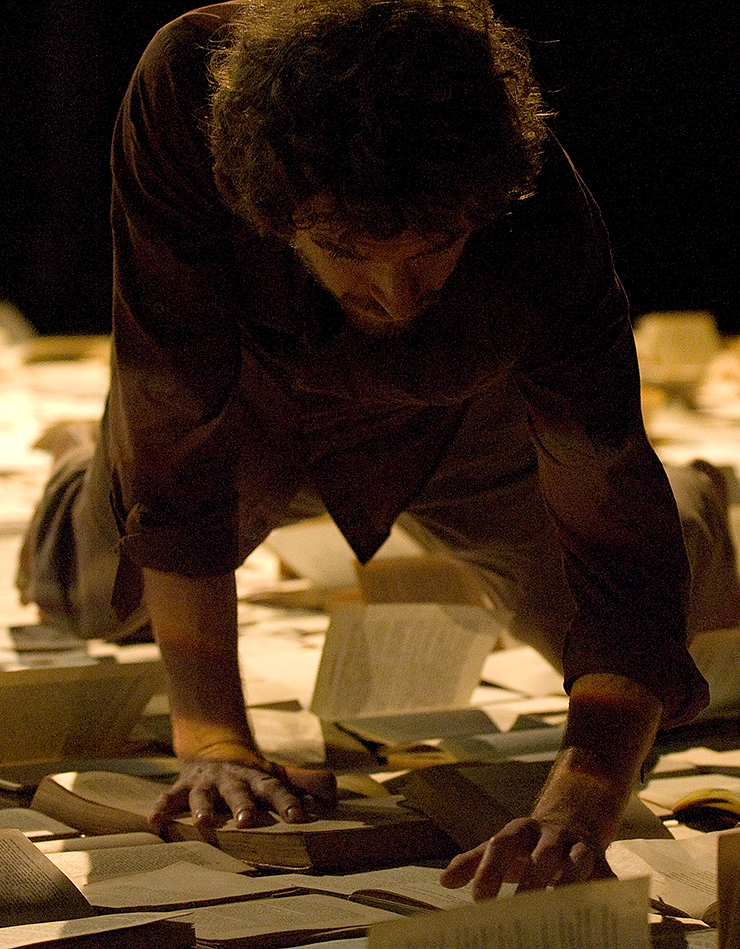

Sunset on Mars © Fred Debrock

Music for dance Mercedes L. Caballero

Protagonists of one of the most categorical and enduring artistic unions, music and dance have been weaving a rich history of stage twinning. Borja Ramos, an outstanding composer of the scene, author of more than forty musical productions for dance, goes through the ins and outs of his approach to this art.

[...] When Borja Ramos (Barakaldo, Spain, 1973), became interested in dance from a professional and musical point of view, Valencia, the city where he lived and studied Fine Arts, was the effervescent focus of emerging and established dance companies and the platform for their exhibition through the Dansa València festival. In an edition of this event, which found in the late 1990s one of its most enriching moments, he began his trajectory as a composer, and only for contemporary dance, he has signed with over forty productions. “There I began to see dance on stage and discovered Damián Muñoz (National Dance Prize 2015). My first approach to this creator was to propose him a video dance piece, since I was studying the branch of Audiovisuals. That work remained unfinished but it was the trigger for me to end up composing the music for several scenes of Daño. That's where it all started,” recalls Ramos, who trained in electro-acoustic composition. Germán Jauregui, 10 & 10 Danza, Idoia Zabaleta, Natalia Medina, Víctor Ullate Ballet, Blanca Arrieta, Matxalen Bilbao, Asier Zabaleta, Cesc Gelabert, with whom he has been working continuously in recent years... all of them have original compositions by Borja Ramos in their choreographic career, which he finds in his relationship with the choreographer, the first step in the development of his work with dance. “The relationship of a choreographer and dancer with music is very special. Very intimate. Sometimes, the engine that makes them work. So the first thing I do is hear how they listen to it. Sometimes a simple poetic pattern, not very narrative, abstract, serves as a starting point. Something very important for me is to carefully plan the means of production I will have, and to introduce them from the beginning as part of the creative process.”

—And how does your process evolve from there?

—In general, the composer needs solitude and concentration. You see rehearsals and then you work in your studio. I also work a lot with video. The important thing about the relationship that is created is how dance and music will dialogue in the viewer's perception.

—How do you establish communication with the dance creator?

—You have to be elastic. You are part of a team and you have to know how to adapt constantly. You have to be generous, to try, to throw material... You can't arrive by imposing a proposal. Once, Cesc Gelabert told me: “the one who asks is not the choreographer, but the show”. And there comes a moment in creation when what you build has its own entity and asks for itself. Your ego can't block that.

—From your experience, does the movement or the music come first?

—In contemporary dance, music usually comes later. The backbone of the discourse is that of movement. And the musician, on that structure, tries to establish a dialogue that should open and multiply the initial proposal. Sometimes it is the other way round: in Cesc Gelabert's La muntanya al teu voltant, for reasons of production, first the music was composed and then the movement. In this way, the music helped to build the movement afterwards.

—What does dance bring to you on a professional level?

—Dance allows me a much more subtle and profound relationship than in theatre and cinema. Music is not just a background ally to provoke emotions. In dance it gives form to the show, it structures it. Composing for dance remains a great pleasure: listening to your work through the body of a performer makes it grow and live in a mysterious way that is difficult to explain.